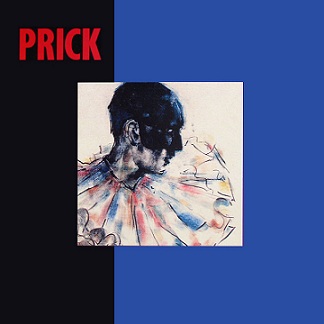

In Conversation is a feature in which the senior staff talk about a record we’ve been listening to. Not exactly a review, it’s pretty much exactly what it says on the tin: two music nerds having a conversation about an album with all the tangential nonsense, philosophical wanking, and hopefully insightful commentary that implies. Nearly twenty years to the week since its release, we revisit the debut eponymous record from Prick, the industrial rock project of Cleveland’s Kevin McMahon, and the first non-Nine Inch Nails release to appear under the Nothing imprint.

Prick

self-titled

Nothing Records

Bruce: I know that for a lot of people, Prick isn’t much more than the random product of the clout Trent Reznor carried at Interscope in the 90s; a favour extended to former bandmate, friend, and mentor Kevin McMahon. You might hear “Animal” out at a more retro-minded industrial club night now and again, but the first Prick album just isn’t discussed that much, and second LP The Wreckard, released seven years later, is almost entirely unknown. But Prick was an integral part of my initiation into industrial music. I have innumerable memories of and associations with “Communiqué”, “No Fair Fights”, and “Makebelieve”, many of which are deeply personal and not of any interest to anyone else, but I think the way in which the record blended ’90s industrial production and rock structures is worth discussing.

Whether I was conscious of it at the time or not, part of what drew me to Prick was how it framed industrial rock as being part of, or at least clearly connected with, extant rock traditions and markers in the broadest sense. As opposed to, say, Skinny Puppy, one of my other recent discoveries and obsessions circa ’96-’98, Kevin McMahon’s music didn’t sound wholly separate from the music I’d heard on the radio all my life…and yet it was still undeniably different from the glam rock and new wave it drew inspiration from (two other genres I was also busy exploring at the time). Unlike industrial metal, itself a hybrid of two “extreme” genres, Prick wears its debt to the smoother (if no less alienated, perhaps) sounds of Bowie and Bolan on its sleeve. In a way, that made Prick a weirder listen than Last Rights, which I understood the place of only by virtue of its complete opposition to music itself as I then understood the term. I didn’t know where Prick fit in in the topos of music, and thus it puzzled and beguiled me.

Two decades on, I realise that by straddling two worlds, Prick was forcing me to pay attention to core compositional structures rather than the production and engineering techniques with which I was, and still am, enchanted (I can’t overstate how much of my taste was formed by Flood and Alan Moulder at a young age). After a few years with Prick I could listen to Pretty Hate Machine and notice just how much it owed to pop songcraft. That seems painfully obvious now, but it would have been blasphemy to my sixteen year-old self, decked out in ripped fishnets and chipped nailpolish. The reasons why Reznor cited Prince as an influence were now plain as day.

So that’s a fair amount of my personal history with Prick. How about you? Did you like it at the time it was released, or was it too “light” in comparison to the heavier industrial punishment you were seeking out?

Alex: I’m gonna level with you: I haven’t listened to this record in probably 17 or 18 years, mostly because at the time it dropped I wasn’t really in a position to figure it out. Like, in ’95 I was still emerging from the shadow of my parent’s taste (and entering a regrettable TRU INDUSTRIAL OR FUCK OFF stage that would last a few years) and my knowledge of the history of rock was woeful to say the least. I guess at the time it just didn’t seem that industrial to me in spite of the Reznor cosign, and was thus of very little interest to me beyond “Animal” which I got familiar with via some limited video play on MuchMusic.

With the benefit of twenty years (good god) of hindsight, it’s pretty easy to position it as you have; where Stabbing Westward was an industrial version of general ’90s mope rock and early Marilyn Manson was a similarly weaponized version of Wasp-esque shock metal, Prick is identifiably a rivet-version of capital-G Glam Rock. I mean you can hear it plain as fucking day on “Tough”: you could easily convince most punters unfamiliar with it that it was a cover of a particularly sleazy Slade b-side or something. My tastes are certainly a lot more developed than they were then and I find on this relisten I’m really finding the mixture a lot more toe-tapping and fun than I did at the time. It’s all about the songwriting and the arrangements, all of which have a lively energy that extends well beyond the T-Rez production touches. It’s worth noting that McMahon was in his forties when this record was released, and had actually been making music steadily since the ’70s with Lucky Pierre amongst others, he came by the glam stuff pretty honestly.

Bruce: Yeah, it’s a weird record just in terms of who made it when and under what conditions. The glammy, baroque new wave pop of McMahon’s early Lucky Pierre records almost feels as far away from Prick as Prick does from The Downward Spiral. Hell, all you have to do is compare the original Lucky Pierre version of “Communiqué” with the Prick one to see how much McMahon was drawing from and was influenced by the high-gloss industrial rock sound his protoge was mining. That said, the question of who should be credited with that distinction is a complex one. While Reznor produced four of the tracks, he certainly wasn’t the only cook in the kitchen. Vet producer Warne Livesey (who’s been at the desk for everyone from Coil to The Creatues to Midnight Oil) helmed the rest, and hell, even the aforementioned Alan Moulder supplied the mix.

Perhaps most instructive is the fact that even after Nothing Records went its titular route, McMahon maintained the distinction between the industrial edges of Prick and the sunnier sides of Lucky Pierre. The Wreckard went into more structurally and conceptually experimental territory (there’s a complex divorce/estrangement concept to the whole thing), but maintained that mix of glammy drama and frantic industrial guitar (“Three Rings”). On the flip side, Lucky Pierre’s 2004 LP ThinKing reprised McMahon’s early quirky pop (“Johnny Goes To Paris”) alongside an awareness of contemporary rock radio (“Beginning”).

But back to Prick. A huge part of what makes my favourite songs on it work is how clearly the music lines up with the emotional thrust of the lyrics, which themselves are an odd mix of naked emotion and almost coded personal reference. McMahon’s great at communicating his narrator(s)’ emotional states and trauma, from the realisation that there’s no high road or noble winner in a break up in “No Fair Fights”, to the manically delusional fantasy of reconciliation imagined in “I Apologise”, to the horrifying disengagement with reality via reverie and nostalgia of “Makebelieve”. Man, in laying it out like that, Prick‘s just about as focused on break-ups and their mental toll as The Wreckard. How’d you relate to the record’s lyrics? Were those running themes what stuck out, or was it more the one-off concept tracks (“Tough”, “Other People”, “Animal”) that represent the album for you?

Alex: I’m not getting as much of the relationship stuff lyrically, although I think my natural inclination is to go with the one-offs you mention anyways, since those tend to be the peppier songs on the record. I mean there isn’t much lyrically to “Tough”, but there doesn’t really need to be, it’s just a classic stomper gussied up with some of that hyper-processed 90’s NIN guitar that was all over The Downward Spiral and its attendant followers, so the light S&M theme of the words is exactly as cheeky as it needs to be. I know a lot of folks (including you) really hold up McMahon as being this amazing poet, but I kinda like him when he’s being a saucy rock guy. Like the way he delivers everything on “Other People”: “I got a red dress yellow dress black dress/I got a closet full of miracles/Pink panties blue panties yellow panties/I’m gonna wrap around your nose“. That’s some silly stuff, but it’s not that far off from being “I’m a street-walking cheetah/with a heart full of napalm” is it? I guess Prick kinda gets to have its cake and eat it too; it’s got some fun dumb rock stuff, and the profound lyrical stuff if you dig into it.

I know some people will probably think I’m being dismissive when I say “dumb rock stuff”, but I mean it in the best possible way. One of the things that has aged exceptionally poorly from the mid-nineties has been just how gosh darn seriously a lot of the pseudo-mainstream industrial took itself. I like that Prick just lets it all hang out, especially in its most famous moment “Animal”. I’ve always enjoyed it, but listening to it right now it strikes me that it’s kind of a perfect single from this band, or at least my idea of what this band is based on my limited investment. It’s big and kinda sexy and I picture it playing in a club while people gyrate in slow motion with a strobe light going off while a detective tries to figure out which of the patrons is the serial killer he’s been tracking. Like, it’s immediate and doesn’t need much to justify or explain itself, and I dig that. I’m curious, do you think our vastly different experiences with this album in terms of affection and overall exposure make it possible for us to see eye to eye on this record? Like, I feel like everything I say is kinda facile, especially when you obviously have spent a ton of time thinking about this LP for like twenty years.

Bruce: Well, I don’t think we’re too far off from each other in the sense that I definitely get that party rock feel from “Tough”, “I Got It Bad”, and others. Much like when I discovered Alien Sex Fiend and realised that goth didn’t have to all be arty miserablism, Prick showed that industrial rock could be fun as well as aggressive. Between that and just how simple and self-contained the lyrical conceit of “Animal” is, I’m not that mad about it still being the one song the majority of industrial fans know about. Yes, I’ve spent years pushing Prick on people who only knew that tune from clubbing, but one facet or another of the record will be left out if you pick just one tune, and “Animal” has a perfect and slinky build.

I couldn’t say with absolute certainty that the reason I’ve spent so much time with this record to the point that it’s a key part of my musical biography is the kooky mix of glam and industrial we’ve discussed, or the “objective” quality of the songwriting rather than the “right sound, right time” happenstance I discussed at the outset. In listening to it with a renewed critical eye over the past week or so, a few flaws come into sharper relief (“Crack” still feels like a warmed-over bit of would-be Zeppelin that never gets out of second gear), but I’ve picked up on plenty of cool moments I probably subconsciously noticed before but had never specifically kept an ear open for: the variety of ways in which guitars are compressed in the mix and then blown up to take everything over on “Riverhead or “Tough” (damn, there’s a good feel for dynamics on this record).

So as this piece has proven, I can talk about this record pretty much ad nauseum, but I feel like your experience of dusting it off after a number of years is probably going to be a lot closer to that of anyone reading this and thinking of tossing it on, so it makes sense that you get the final word on Prick‘s legacy and how it sounds twenty years on.

Alex: Well I ain’t wanna overstate it like “Oh yeah, this is a lost treasure given short shrift in its day”. I think the general perception of the album is that it’s pretty good, and it’s a lot less obscure than plenty of stuff from the era. I think the big takeaway I can offer from this whole exercise is that this album is a lot funner and has a lot more style than plenty of the albums it gets lumped in with. Though with that said, that weird period in the 90’s when industrial rock had its abortive day in the sun produced very few actual gems LP-wise, and this might be deserving of canonization if you’re talking about Our Thing’s middle history.

You could actually leave Prick out of that discussion entirely though, and position it as part of the broader recognition of glam in the 90’s. Strikes me it was around that time that Bowie really ascended into the broader Gen Y consciousness, and you heard all kinds of stuff like Placebo that was wearing the influence pretty proudly. I’m no expert on it (as mentioned I was in the midst of seriously ghettoizing my own taste at the time), but I suppose the fact that it easily fits into two distinct histories within popular music is enough to recommend it to anyone who might be unfamiliar or just plain forgotten about it. It’s a unique bird, and you don’t need to be a birdwatcher to admire the plumage.

Great piece on an underappreciated gem! I bought this album when it first came out and I still enjoy listening to it from time to time. It’s such a fun record, and I love the top notch songwriting and production. As far as Nothing releases go, I’d say this is a great companion to PWEI’s Dos Dedos Mix Amigos.

“With the benefit of twenty years (good god) of hindsight, it’s pretty easy to position it as you have; where Stabbing Westward was an industrial version of general ’90s mope rock and early Marilyn Manson was a similarly weaponized version of Wasp-esque shock metal, Prick is identifiably a rivet-version of capital-G Glam Rock.”

Now there’s a subject that deserves its own essay! Chemlab was another good band that you could easily connect to mainstream rock lineages outside of industrial. I think NIN is a bit harder to reduce to just “the industrialized version of ______”- the mainstream rock influences are there, obviously, but he combined so many of them from all over the place. I guess it makes sense then that NIN was the most popular industrial rock band. There was probably a turning point in the history of the subgenre when someone made an industrial rock album that was only influenced by previous industrial rock, rather than influenced by industrial and rock separately (any guesses to when/who that was?). Maybe that’s when it went from a really vital style to more of a niche market.

A question I’ve had for a while now: Are there any bands that are a) indisputably “industrial rock” bands, and b) heavily and indisputably influenced by any distinctly 21st century styles of non-industrial rock music? Aside from maybe NIN? If not, is it just because there hasn’t been much innovation in 21st century rock that’s deserving of being industrialized?

Well, it’a a loaded topic, but imagine a filmmaker who makes a z genre film that’s soley influenced by genre z features. Note that genre z in itself was also influenced by x and y. Does our filmmaker’s understanding of x and y come only from z? That might be a bad sign.

Solely, not soley. 😉

That’s a really interesting question, and I struggled mightily trying to come up with an answer, but I thought it was such an interesting question that I’m responding anyways!

I’ve still got nothing.

And I think you’re right about the stagnation in 21st century rock. On the flip side, I don’t listen to much metal, but there’s a lot of interesting things happening there. We might look to them.

For example, see Gojira maybe: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkass5pLUnI

I wouldn’t call it industrial rock. But this mechanical, technical metal is very, very good and it sounds fresh.